奇異恩典 Amazing Grace

奇異恩典

《奇異恩典》(Amazing Grace)是其中一首最著名的基督教聖詩。歌詞為約翰·牛頓所填,出現在威廉·科伯(William Cowper)及其他作曲家創作的讚美詩集Olney Hymns的一部分。

目錄[隐藏] |

[編輯] 歷史

約翰·牛頓(1725年—1807年)曾經是一艘奴隸船的船長。在1748年5月10日歸家途中遇到了暴風雨,他經歷了「偉大的判決」。在他的航海日誌中他寫道:他的船處在即將沉沒的重大危險中,他喊道「主憐憫我們」。他的內心逐漸走向光明,但他在這次劫難之後,最後仍然賣掉了這船的奴隸。

在非洲一個港口等待奴隸裝船的時候,牛頓寫下了歌曲《耶穌之名如此美妙》。以後,他和奴隸貿易切斷了關係,當上了一名牧師,並且加入了威廉·威伯福斯領導的反奴隸運動。

這首讚美詩也在美國黑人基督教社會流傳。最初這首讚美詩選用過20多種旋律,到1835年的時候,借用了《新不列顛》的曲調,廣泛流傳直到今天。

[編輯] 歌詞

| 原文 | 中譯版本1 | 中譯版本2 | 中譯版本3 | 中譯版本4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound) | 奇異恩典,樂聲何等甜美 | 奇異恩典,甘似蜜甜, | 驚人恩典!何等甘甜, | 奇異恩典,何等甘甜, |

[編輯] 文藝作品

- 2006年英國電影Amazing Grace,導演Michael Apted,主演Ioan Gruffudd,再現了威廉·威伯福斯的反販奴運動,以及牛頓牧師寫作這首歌詞的過程。

[編輯] 外部連結

- 約翰·牛頓-Amazing Grace

- Amazing Grace: The Story of John Newton

- Who Has Recorded Amazing Grace?

- Easybyte - free easy piano arrangement of Amazing Grace

- Amazing Grace myths at the Urban Legends Reference Pages

- Art of the States: Amazing Grace variations on the hymn by composer John Harbison

アメイジング・グレイス

アメイジング・グレイス(英語:Amazing Grace, 和訳例:すばらしき恩寵)は、ジョン・ニュートンの作詞による賛美歌である。特にアメリカで愛唱され、またバグパイプでも演奏される。"grace"とは「神の恵み」「恩寵」の意。

- 原詞詞名(初行): Amazing grace! how sweet the sound

- 曲名(チューンネーム): NEW BRITAIN または AMAZING GRACE

- ミーター:86 86 (CM)

目次[非表示] |

成立 [編集]

作詞者はジョン・ニュートン (John Newton)。作曲者は不詳。アイルランドかスコットランドの民謡を掛け合わせて作られたとしたり、19世紀に南部アメリカで作られたとするなど、諸説がある。

ジョン・ニュートンは1725年、イギリスに生まれた。母親は幼いジョンに聖書を読んで聞かせるなど敬虔なクリスチャンだったが、ジョンが7歳の時に亡くなった。成長したジョンは、商船の指揮官であった父に付いて船乗りとなったが、さまざまな船を渡り歩くうちに黒人奴隷を輸送するいわゆる「奴隷貿易」に手を染め巨万の富を得るようになった。

当時奴隷として拉致された黒人への扱いは家畜以下であり、輸送に用いられる船内の衛生環境は劣悪であった。このため多くの者が輸送先に到着する前に感染症や脱水症状、栄養失調などの原因で死亡したといわれる。

ジョンもまたこのような扱いを拉致してきた黒人に対して当然のように行っていたが、1748年5月10日、彼が22歳の時に転機はやってきた。船長として任された船が嵐に遭い、非常に危険な状態に陥ったのである。今にも海に呑まれそうな船の中で、彼は必死に神に祈った。敬虔なクリスチャンの母を持ちながら、彼が心の底から神に祈ったのはこの時が初めてだったという。すると船は奇跡的に嵐を脱し、難を逃れたのである。彼はこの日をみずからの第二の誕生日と決めた。その後の6年間も、ジョンは奴隷を運び続けた。しかし彼の船に乗った奴隷への待遇は、動物以下の扱いではあったものの、当時の奴隷商としては飛躍的に改善されたという。

1755年、ジョンは病気を理由に船を降り、勉学と多額の寄付を重ねて牧師となった。そして1772年、「アメイジング・グレイス」が生まれたのである[1]。この曲には、黒人奴隷貿易に関わったことに対する深い悔恨と、それにも関わらず赦しを与えた神の愛に対する感謝が込められているといわれている。

この曲のほかにも、彼はいくつかの賛美歌を遺している。

所収 [編集]

サンプル [編集]

- 聴く(アメイジング・グレイス)ニューヨーク州デラウウェア郡出身のアマチュア・デュオ「ロック・フローム・ザ・ガーデン」による演奏。ボーカルがジョアニーさんで、ギターがランディーさん。2分53秒

- 聴く(アメイジング・グレイス)パイプ・オルガンのみによる伴奏。32秒

- うまく聞けない場合は、サウンド再生のヒントをご覧ください。

有名な歌唱など [編集]

CD・レコード音源 [編集]

- マヘリア・ジャクソン - 1947年に録音。

- ジュディ・コリンズ - 1970年にセント・ポール教会にてアカペラで歌い、アルバム『Whales & Nightingales』に収録。1971年1月9日付ビルボード・ホット100で最高15位を記録した。イギリスでは67週チャートインを達成した。

- アレサ・フランクリン - 1972年のライブアルバム『Amazing Grace』で歌い、ゴスペルの名盤の一つとなっている。

- ナナ・ムスクーリ - 1972年のアルバム『BRITISH CONCERT』の中でア・カペラで唄い日本でも発売された。その後伴奏付の COUREUR GOSPELなどでの収録分がテレビCMなどに使われた。

- ロイヤル・スコッツ・ドラゴン・ガーズ - 1972年にカバーし、同年5月27日付ビルボード・ホット100で最高11位、全世界でレコード売上700万枚を記録した。邦題は「スコットランドの夕やけ(至上の愛)」。

- さだまさし - 1987年に発表したシングル『風に立つライオン』の間奏部およびラストに引用。

- 綾戸智絵 - 1999年のアルバムに収録。彼女の代表的なレパートリーの一つ。

- 中島美嘉 - 2001年のドラマデビュー作『傷だらけのラブソング』の中でア・カペラで歌って話題を集め、翌年発売の2ndシングル『CRESCENT MOON』と1stアルバム『TRUE』に収録。2005年に発売のベストアルバムでは綾戸智絵のプロデュースで再録音した。

- ヘイリー・ウェステンラ - 2003年に放送されたドラマ『白い巨塔』となり、エンディング・テーマとしてシングル発売されたほか、サントラアルバムにも収録。2008年5月21日発売のシングル「アメイジング・グレイス2008」では本田美奈子が残した音源との仮想的なデュエットを果たしている。

- 本田美奈子. - クラシックアルバムの第一作『AVE MARIA』に収録。白血病で闘病中の2005年10月に発売されたベストアルバム『アメイジング・グレイス』にも収録された。後者は11月の逝去後売り上げが急増し、オリコンチャートでベスト10入りを果たした。入院中に病室で歌ったア・カペラの「アメイジング・グレイス」は2006年7月から一年間、公共広告機構(現:ACジャパン)の骨髄バンク支援キャンペーンのテレビコマーシャルに使用された。

- mink - 2005年にコンセプトアルバム『e+motion』に収録。ライブではしばしば披露されており、2007年にはフジテレビ系『僕らの音楽』でテレビ初披露した。

- NUM42 - 2006年のアルバム『PUNK MASH UP!』に収録。NUMBER.42に改名後の2010年のアルバム『PUNK ROCK NEVER DIE』にも収録された。

- 宮良牧子 - 2008年に発表したアルバム『マブイウタ』にて沖縄方言ヴァージョン(作詞・島幸子)で収録。

ライブでのみ披露 [編集]

- ジョーン・バエズ - 1985年7月13日に開催されたライヴエイドのフィラデルフィア会場でのオープニングで歌唱。

- 藤本美貴 - 2006年のディナーショーにて披露。この模様はテレビ番組『娘DOKYU!』にて、歌唱練習シーンも含めて放送された。

- 古謝美佐子・夏川りみ - コンサートにて沖縄方言ヴァージョンをデュエットで歌った。

劇中歌など [編集]

- メリル・ストリープ - 1983年の映画『シルクウッド』で歌った。

- 白鳥英美子 - 1987年、ア・カペラで歌ったものがCM曲に起用された。

- 河井英里 - 2005年にSEGAから発売されたPS2用ソフト「龍が如く」のエンディング曲として歌唱。

- 堀澤麻衣子 - 2006年のアニメ『交響詩篇エウレカセブン』第4期OPで、NIRGILISが歌う『sakura』とマッシュアップされている。

- 永澤俊矢 - ドラマ『エトロフ遥かなり』で、長澤演じる主人公のケニー斉藤がハーモニカで演奏していた。

- 演奏者不明 - 2002年1月27日放送の『仮面ライダーアギト』の最終回で、前半部分が演奏されている。

- 演奏者不明 - 2007年発売のゲーム『そして明日の世界より――』でafterシナリオのEDテーマソングに使用された。

- 演奏者不明 - 2008年4月19日公開の『名探偵コナン 戦慄の楽譜』のストーリーに関わる重要な挿入歌として、パイプオルガンとバイオリンの伴奏付きで使用されている。のびやかなオペラ版のこの曲は、同映画のサウンドトラックにも収録されている。

- 演奏者不明 - 2009年放送のアニメ『空中ブランコ』第10話の劇中でBGMとして使用された。

- 演奏者不明 - 2010年放送のアニメ『ソ・ラ・ノ・ヲ・ト』の劇中で象徴的BGMとして複数回使用。

- 演奏者不明 - ニンテンドーDSのゲーム『もっとえいご漬け』に聞き取りトレーニングメニューとして1番が収録されている。

- Jリーグ・ジェフユナイテッド千葉のサポーターのチャントとして使われている。

- 演奏者不明 - 2010年公開の映画『マルドゥック・スクランブル』の主題歌として使われている。

脚注 [編集]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Amazing Grace

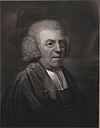

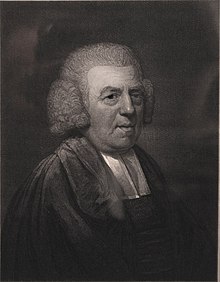

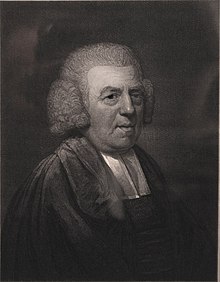

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn written by English poet and clergyman John Newton (1725–1807), published in 1779. With a message that forgiveness and redemption are possible regardless of the sins people commit and that the soul can be delivered from despair through the mercy of God, "Amazing Grace" is one of the most recognizable songs in the English-speaking world.

Newton wrote the words from personal experience. He grew up without any particular religious conviction but his life's path was formed by a variety of twists and coincidences that were often put into motion by his recalcitrant insubordination. He was pressed into the Royal Navy and became a sailor, eventually participating in the slave trade. One night a terrible storm battered his vessel so severely that he became frightened enough to call out to God for mercy, a moment that marked the beginning of his spiritual conversion. His career in slave trading lasted a few years more until he quit going to sea altogether and began studying theology.

Ordained in the Church of England in 1764, Newton became curate of Olney, Buckinghamshire, where he began to write hymns with poet William Cowper. "Amazing Grace" was written to illustrate a sermon on New Year's Day of 1773. It is unknown if there was any music accompanying the verses, and it may have been chanted by the congregation without music. It debuted in print in 1779 in Newton and Cowper's Olney Hymns, but settled into relative obscurity in England. In the United States however, "Amazing Grace" was used extensively during the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century. It has been associated with more than 20 melodies, but in 1835 it was joined to a tune named "New Britain" to which it is most frequently sung today.

Author Gilbert Chase writes that "Amazing Grace" is "without a doubt the most famous of all the folk hymns",[1] and Jonathan Aitken, a Newton biographer, estimates that it is performed about 10 million times annually.[2] It has had particular influence in folk music, and become an emblematic African American spiritual. Its universal message has been a significant factor in its crossover into secular music. "Amazing Grace" saw a resurgence in popularity in the U.S. during the 1960s and has been recorded thousands of times during and since the 20th century, sometimes appearing on popular music charts.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] John Newton's conversion

How industrious is Satan served. I was formerly one of his active undertemptors and had my influence been equal to my wishes I would have carried all the human race with me. A common drunkard or profligate is a petty sinner to what I was.

According to the Dictionary of American Hymnology "Amazing Grace" is John Newton's spiritual autobiography in verse.[4] In 1725, Newton was born in Wapping, a district in London near the Thames. His father was a shipping merchant who was brought up as a Catholic but had Protestant sympathies, and his mother was a devout Independent unaffiliated with the Anglican Church. She had intended Newton to become a clergyman, but she died of tuberculosis when Newton was six years old.[5] For the next few years, Newton was raised by his distant stepmother while his father was at sea, and spent some time at a boarding school where he was mistreated.[6] At the age of eleven, he joined his father on a ship as an apprentice; his seagoing career would be marked by headstrong disobedience.

As a youth, Newton began a pattern of coming very close to death, examining his relationship with God, then relapsing into bad habits. As a sailor, he denounced his faith after being influenced by a shipmate who discussed Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times, a book by the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, with him. In a series of letters he later wrote, "Like an unwary sailor who quits his port just before a rising storm, I renounced the hopes and comforts of the gospel at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail me."[7] His disobedience caused him to be pressed into the Royal Navy, and he took advantage of opportunities to overstay his leave and finally deserted to visit Mary "Polly" Catlett, a family friend with whom he had fallen in love.[8] After enduring humiliation for deserting,[note 1] he managed to get himself traded to a slave ship where he began a career in slave trading.[note 2]

Newton often openly mocked the captain by creating obscene poems and songs about him that became so popular the crew began to join in.[9] He entered into disagreements with several colleagues which resulted in his being nearly starved to death, imprisoned while at sea and chained like the slaves they carried, then outright enslaved and forced to work on a plantation in Sierra Leone near the Sherbro River. After several months he came to think of Sierra Leone as his home, but his father intervened after Newton sent him a letter describing his circumstances, and a ship found him by coincidence.[note 3] Newton claimed the only reason he left was because of Polly.[10]

While aboard the ship Greyhound, Newton gained notoriety for being one of the most profane men the captain had ever met. In a culture where sailors commonly used oaths and swore, Newton was admonished several times for not only using the worst words the captain had ever heard, but creating new ones to exceed the limits of verbal debauchery.[11] In March 1748, while the Greyhound was in the North Atlantic, a violent storm came upon the ship that was so rough it swept overboard a crew member who had been standing where Newton was moments before.[note 4] After hours of the crew emptying water from the ship and expecting to be capsized, he offered a desperate suggestion to the captain, who ordered it so. Newton turned and said, "If this will not do, then Lord have mercy upon us!"[12][13] He returned to the pump where he and another mate tied themselves to it to keep from being washed over. After an hour's rest, an exhausted Newton returned to the deck to steer for the next eleven hours where he pondered what he had said.[14]

About two weeks later, the battered ship and starving crew landed in Lough Swilly, Ireland. For several weeks before the storm, Newton had been reading The Christian’s Pattern, a summary of the 15th-century The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. The memory of the uttered phrase in a moment of desperation did not leave him; he began to ask if he was worthy of God's mercy or in any way redeemable as he had not only neglected his faith but directly opposed it, mocking others who showed theirs, deriding and denouncing God as a myth. He came to believe that God had sent him a profound message and had begun to work through him.[15]

Newton's conversion was not immediate, but he contacted Polly's family and announced his intentions to marry her. Her parents were hesitant as he was known to be unreliable and impetuous. They knew he was profane, but they allowed him to write to Polly, and he set to begin to submit to authority for her sake.[16] He sought a place on a slave ship bound for Africa, and Newton and his crewmates participated in most of the same activities he had written about before; the only action he was able to free himself from was profanity. After a severe illness his resolve was renewed yet he retained the same attitude about slavery as his contemporaries[note 5] and continued in the trade through several voyages where he sailed up rivers in Africa—now as a captain—procured slaves being offered and sold them in larger ports to be sent to North or South America. In between voyages, he married Polly in 1750 and he found it more difficult to leave her at the beginning of each trip. After three shipping experiences in the slave trade, Newton was promised a position as a captain on a ship with cargo unrelated to slavery, when at thirty years old, he collapsed and never sailed again.[17][note 6]

[edit] Olney curate

Working as a customs agent in Liverpool starting in 1756, Newton began to teach himself Latin, Greek, and theology. He and Polly immersed themselves in the church community and Newton's passion was so impressive that his friends suggested he become a minister. He was turned down by the Bishop of York in 1758, ostensibly for having no university degree,[18] although the more likely reasons were his leanings toward evangelism and tendency to socialize with Methodists.[19] Newton continued his devotions, and after being encouraged by a friend, he wrote about his experiences in the slave trade and his conversion. The Earl of Dartmouth, impressed with his story, sponsored Newton for ordination with the Bishop of Lincoln, and offered him the curacy of Olney, Buckinghamshire in 1764.[20]

[edit] Olney Hymns

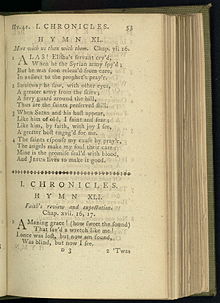

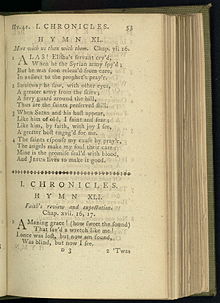

Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav'd a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

'Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

And grace my fears reliev'd;

How precious did that grace appear

The hour I first believ'd!

Thro' many dangers, toils, and snares,

I have already come;

'Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far,

And grace will lead me home.

The Lord has promis'd good to me,

His word my hope secures;

He will my shield and portion be

As long as life endures.

Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail,

And mortal life shall cease;

I shall possess, within the veil,

A life of joy and peace.

The earth shall soon dissolve like snow,

The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call'd me here below,

Will be forever mine.

Olney was a hamlet of about 2,500 residents whose main industry was making lace by hand. They were mostly illiterate and many of them were poor.[2] Newton's preaching was unique in that he shared many of his own experiences from the pulpit; many clergy preached from a distance, not admitting any intimacy with temptation or sin. He was involved in his parishioners' lives and he was much loved although his writing and delivery were sometimes unpolished.[21] His devotion and conviction were apparent and forceful however, and his mission he often said was to "break a hard heart and to heal a broken heart".[22] He struck a friendship with William Cowper, a gifted writer who had failed at a career in law and suffered bouts of insanity, attempting suicide several times. Cowper enjoyed Olney—and Newton's company; he was also new to Olney and had gone through a spiritual conversion similar to Newton's. Together, their effect on the local congregation was impressive. In 1768, they found it necessary to start a weekly prayer meeting in order to meet the needs of an increasing number of parishioners. They also began writing lessons for children.[23]

Partly from Cowper's literary influence, and partly because learned vicars were expected to write verses, Newton began to try his hand at hymns, which had become popular through the language, made plain for common people to understand. Several prolific hymn writers were at their most productive in the 18th century, including Isaac Watts—whose hymns Newton had grown up hearing[24]—and Charles Wesley, with whom Newton was familiar. Wesley's brother John, the eventual founder of the Methodist Church, had encouraged Newton to go into the clergy.[note 7] Watts was a pioneer in English hymn writing, basing his on the Psalms. The most prevalent hymns by Watts and others were written in the common meter in 8.6.8.6: the first line is eight syllables and the second is six.[25]

Newton and Cowper attempted to present a poem or hymn for each prayer meeting. The lyrics to "Amazing Grace" were written in late 1772 and probably used in a prayer meeting for the first time on January 1, 1773.[25] A collection of the poems Newton and Cowper had written for use in services at Olney were bound and published anonymously in 1779 under the title Olney Hymns. Newton contributed 280 of the 348 texts in Olney Hymns; "1 Chronicles 17:16–17, Faith's Review and Expectation" was the title of the poem with the first line "Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)".[4]

[edit] Critical analysis

The general impact of Olney Hymns was immediate and it became a widely popular tool for evangelicals in Britain for many years. Scholars appreciated Cowper's poetry somewhat more than Newton's plaintive and plain language driven from his forceful personality. The most prevalent themes in the verses written by Newton in Olney Hymns are faith in salvation, wonder at God's grace, his love for Jesus, and his ebullient exclamations of the joy he found in his faith.[26] As a reflection of Newton's connection to his parishioners, he wrote many of the hymns in first person, admitting his own experience with sin. Bruce Hindmarsh in Sing Them Over Again To Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America considers "Amazing Grace" an excellent example of Newton's testimonial style afforded by the use of this perspective.[27] Several of Newton's hymns were recognized as great work ("Amazing Grace" was not among these) while others seem to have been included to fill in when Cowper was unable to write.[28] Jonathan Aitken calls Newton, specifically referring to "Amazing Grace", an "unashamedly middlebrow lyricist writing for a lowbrow congregation", noting that only twenty-one of the words used in all six verses have more than one syllable.[29]

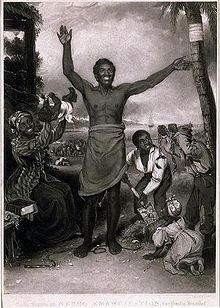

William Phipps in the Anglican Theological Review and author James Basker have interpreted the first stanza of "Amazing Grace" as evidence of Newton's realization that his participation in the slave trade was his wretchedness, perhaps representing a wider common understanding of Newton's motivations.[30][31] Newton joined forces with a young man named William Wilberforce, the British Member of Parliament who led the Parliamentarian campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire, culminating in the Slave Trade Act 1807. However, Newton became an ardent and outspoken abolitionist after he left Olney in the 1780s; he never connected the construction of the hymn that became "Amazing Grace" to anti-slavery sentiments.[32] The lyrics in Olney Hymns were arranged by their association to the Biblical verses that would be used by Newton and Cowper in their prayer meetings and did not address any political objective. For Newton, the beginning of the year was a time to reflect on one's spiritual progress. At the same time he completed a diary—which has since been lost—that he had begun 17 years before, two years after he quit sailing. The last entry of 1772 was a recounting of how much he had changed since then.[33]

And David the king sat before the Lord, and said, "Who am I, O Lord God, and what is mine house, that thou hast brought me hitherto? And yet this was a small thing in thine eyes, O God; for thou hast also spoken of thy servant's house for a great while to come, and hast regarded me according to the estate of a man of high degree, O Lord God.

The title ascribed to the hymn, "1 Chronicles 17:16–17", refers to David's reaction to the prophet Nathan telling him that God intends to maintain his family line forever. Some Christians interpret this as a prediction that Jesus Christ, as a descendant of David, was promised by God as the salvation for all people.[34] Newton's sermon on that January day in 1773 focused on the necessity to express one's gratefulness for God's guidance, that God is involved in the daily lives of Christians though they may not be aware of it, and that patience for deliverance from the daily trials of life is warranted when the glories of eternity await.[35] Newton saw himself a sinner like David who had been chosen, perhaps undeservedly,[36] and was humbled by it. According to Newton, unconverted sinners were "blinded by the god of this world" until "mercy came to us not only undeserved but undesired ... our hearts endeavored to shut him out till he overcame us by the power of his grace."[33]

The New Testament served as the basis for many of the lyrics of "Amazing Grace". The first verse, for example, can be traced to the story of the Prodigal Son. In the Gospel of Luke the father says, "For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost, and is found". The story of Jesus healing a blind man who tells the Pharisees that he can now see is told in the Gospel of John. Newton used the words "I was blind but now I see" and declared "Oh to grace how great a debtor!" in his letters and diary entries as early as 1752.[37] The effect of the lyrical arrangement, according to Bruce Hindmarsh, allows an instant release of energy in the exclamation "Amazing grace!", to be followed by a qualifying reply in "how sweet the sound". In An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, Newton's use of an expletive at the beginning of his verse is called "crude but effective" in an overall composition that "suggest(s) a forceful, if simple, statement of faith".[36] Grace is recalled three times in the following verse, culminating in Newton's most personal story of his conversion, underscoring the use of his personal testimony with his parishioners.[27]

The sermon preached by Newton was the last of his William Cowper heard in Olney for Cowper's mental instability returned shortly thereafter. Steve Turner, author of Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, suggests Newton may have had his friend in mind, employing the themes of assurance and deliverance from despair for Cowper's benefit.[38]

[edit] Dissemination

Although it had its roots in England, "Amazing Grace" became an integral part of the Christian tapestry in the United States. More than 60 of Newton and Cowper's hymns were republished in other British hymnals and magazines, but "Amazing Grace" was not, appearing only once in a 1780 hymnal sponsored by the Countess of Huntingdon. Scholar John Julian commented in his 1892 A Dictionary of Hymnology that outside of the United States, the song was unknown and it was "far from being a good example of Newton's finest work".[39][note 8] Between 1789 and 1799, four variations of Newton's hymn were published in the U.S. in Baptist, Dutch Reformed, and Congregationalist hymnodies;[34] by 1830 Presbyterians and Methodists also included Newton's verses in their hymnals.[40][41]

The greatest influences in the 19th century that propelled "Amazing Grace" to spread across the U.S. and become a staple of religious services in many denominations and regions were the Second Great Awakening and the development of shape note singing communities. A tremendous religious movement was overtaking the U.S. in the early 19th century that was marked by growth and popularity of churches and religious revivals that got their start in Kentucky and Tennessee. Unprecedented gatherings of thousands of people attended camp meetings where they came to experience salvation; preaching was fiery and focused on saving the sinner from temptation and backsliding.[42] Religion was stripped of ornament and ceremony, and made as plain and simple as possible; sermons and songs often used repetition to get across to a rural population of poor and mostly uneducated people the necessity of turning away from sin. Witnessing and testifying became an integral component to these meetings, where a congregation member or even a stranger would rise and recount his turn from a sinful life to one of piety and peace.[40] "Amazing Grace" was one of many hymns that punctuated fervent sermons, although the contemporary style used a refrain, borrowed from other hymns, that employed simplicity and repetition such as:

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind but now I see.

Shout, shout for glory,

Shout, shout aloud for glory;

Brother, sister, mourner,

All shout glory hallelujah.[42]

Simultaneously, an unrelated movement of communal singing was established throughout the South and Western states. A format of teaching music to illiterate people appeared in 1800. It used four sounds to symbolize the basic scale: fa-sol-la-fa-sol-la-mi-fa. Each sound was accompanied by a specifically shaped note and thus became known as shape note singing. The method was simple to learn and teach, so schools were established throughout the South and West. Communities would come together for an entire day of singing, to a large building where they sat in four distinct areas surrounding an open space with one member directing the group as a whole. Most of the music was religious, but the purpose of communal singing was not primarily spiritual. Communities either could not afford music accompaniment or rejected it out of a Calvinistic sense of simplicity, so the songs were sung a cappella.[43]

[edit] "New Britain" tune

When originally used in Olney, it is unknown what music, if any, accompanied the verses written by John Newton. At the time, hymnbooks did not contain music and were simply small books of religious poetry. The first known instance of Newton's lines joined to music was in A Companion to the Countess of Huntingdon’s Hymns (London, 1808), where it is set to the tune "Hephzibah" by English composer John Jenkins Husband.[44] Common meter hymns were interchangeable with a variety of tunes; more than twenty musical settings of "Amazing Grace" circulated with varying popularity until 1835 when William Walker assigned Newton's words to a traditional song named "New Britain", which was itself an amalgamation of two melodies ("Gallaher" and "St. Mary") first published in the Columbian Harmony by Charles H. Spilman and Benjamin Shaw (Cincinnati, 1829). Spilman and Shaw, both students at Kentucky's Centre College, compiled their tunebook both for public worship and revivals, to satisfy "the wants of the Church in her triumphal march." Most of the tunes had been previously published, but "Gallaher" and "St. Mary" had not.[45] As neither tune is attributed, and both show elements of oral transmission, scholars can only speculate on the tune's origins. These guesses include a Scottish folk ballad as many of the new residents of Kentucky and Tennessee were immigrants from Scotland,[46] or folk songs developed in Virginia,[47] or South Carolina, William Walker's home state.[48]

"Amazing Grace", with the words written by Newton and joined with "New Britain", the melody most currently associated with it, appeared for the first time in Walker's shape note tunebook Southern Harmony.[48] It was, according to author Steve Turner, a "marriage made in heaven...The music behind 'amazing' had a sense of awe to it. The music behind 'grace' sounded graceful. There was a rise at the point of confession, as though the author was stepping out into the open and making a bold declaration, but a corresponding fall when admitting his blindness."[49] Walker's collection was enormously popular, selling about 600,000 copies all over the U.S. when the total population was just over 20 million. Another shape note tunebook named The Sacred Harp (1844) by Georgia residents Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King became widely influential and continues to be used.[50]

Another verse was first recorded in Harriet Beecher Stowe's immensely influential 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Three verses were emblematically sung by Tom in his hour of deepest crisis.[51] He sings the sixth and fifth verses in that order, and Stowe included another verse not written by Newton that had been passed down orally in African American communities for at least 50 years. It was originally one of between 50 to 70 verses of a song titled "Jerusalem, My Happy Home" that first appeared in a 1790 book called A Collection of Sacred Ballads:

"Amazing Grace" came to be an emblem of a religious movement and a symbol of the U.S. itself as the country was involved in a great political experiment, attempting to employ democracy as a means of government. Shape note singing communities, with all the members sitting around an open center, each song employing a different director, illustrated this in practice. Simultaneously, the U.S. began to expand westward into previously unexplored territory that was often wilderness. The "dangers, toils, and snares" of Newton's lyrics had both literal and figurative meanings for Americans.[50] This became poignantly true during the most serious test of American cohesion in the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" was included in two hymnals distributed to soldiers and with death so real and imminent, religious services in the military became commonplace.[54]

[edit] Urban revival

| This recording was done for the Archive of American Folk-Song in Livingston, Alabama in 1939, and is in the U.S. Library of Congress |

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Although "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" was popular, other versions existed regionally. Primitive Baptists in the Appalachian region often used "New Britain" with other hymns, and sometimes sing the words of "Amazing Grace" to other folk songs, including titles such as "In the Pines", "Pisgah", "Primrose", and "Evan", as all are able to be sung in common meter, of which the majority of their repertoire consists.[55][56] A tune named "Arlington" accompanied Newton's verses as much as "New Britain" for a time in the late 19th century.

Two musical arrangers named Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey heralded another religious revival in the cities of the U.S. and Europe, giving the song international exposure. Moody's preaching and Sankey's musical gifts were significant; their arrangements were the forerunners of gospel music, and churches all over the U.S. were eager to acquire them.[57] Moody and Sankey began publishing their compositions in 1875, and "Amazing Grace" appeared three times with three different melodies, but they were the first to give it its title; hymns were typically published using the first line of the lyrics, or the name of the tune such as "New Britain". A publisher named Edwin Othello Excell gave the version of "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" immense popularity by publishing it in a series of hymnals that were used in urban churches. Excell altered some of Walker's music, making it more contemporary and European, giving "New Britain" some distance from its rural folk-music origins. Excell's version was more palatable for a growing urban middle class and arranged for larger church choirs. Several editions featuring Newton's first three stanzas and the verse previously included by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom's Cabin were published by Excell between 1900 and 1910, and his version of "Amazing Grace" became the standard form of the song in American churches.[58][59]

[edit] Recorded versions

With the advent of recorded music and radio, "Amazing Grace" began to cross over from primarily a gospel standard to secular audiences. The ability to record combined with the marketing of records to specific audiences allowed "Amazing Grace" to take on thousands of different forms in the 20th century. Where Edwin Othello Excell sought to make the singing of "Amazing Grace" uniform throughout thousands of churches, records allowed artists to improvise with the words and music specific to each audience. Allmusic lists more than 6,000 versions of the song as of May 2010.[60] Its first recording is an a cappella version from 1922 by the Sacred Harp Choir. It was included from 1926 to 1930 in Okeh Records' catalog, which typically concentrated strongly on blues and jazz. Demand was high for black gospel recordings of the song by H.R. Tomlin and J. M. Gates. A poignant sense of nostalgia accompanied the recordings of several gospel and blues singers in the 1940s and 1950s who used the song to remember their grandparents, traditions, and family roots.[61] It was recorded with musical accompaniment for the first time in 1930 by Fiddlin' John Carson, although to another folk hymn named "At the Cross", not to "New Britain".[62] "Amazing Grace" is emblematic of several kinds of folk music styles, often used as the standard example to illustrate such musical techniques as lining out and call and response, that have been practiced in both black and white folk music.[63]

Those songs come out of conviction and suffering. The worst voices can get through singing them 'cause they're telling their experiences.

Gospel superstar Mahalia Jackson's 1947 version received significant radio airplay, and as her popularity grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, she often sang it at public events such as concerts at Carnegie Hall.[65] Author James Basker states that the song has been employed by African Americans as the "paradigmatic Negro spiritual" because it expresses the joy felt at being delivered from slavery and worldly miseries.[31] Anthony Heilbut, author of The Gospel Sound, states that the "dangers, toils, and snares" of Newton's words are a "universal testimony" of the African American experience.[66] In the 1960s with the African American Civil Rights Movement and opposition to the Vietnam War, the song took on a political tone. Mahalia Jackson employed "Amazing Grace" for Civil Rights marchers, writing that she used it "to give magical protection—a charm to ward off danger, an incantation to the angels of heaven to descend.... I was not sure the magic worked outside the church walls ... in the open air of Mississippi. But I wasn't taking any chances."[67] Folk singer Judy Collins, who knew the song before she could remember learning it, witnessed Fannie Lou Hamer leading marchers in Mississippi in 1964, singing "Amazing Grace". Collins also considered it a talisman of sorts, and saw its equal emotional impact on the marchers, witnesses, and law enforcement who opposed the civil rights demonstrators.[3] According to fellow folk singer Joan Baez, it was one of the most requested songs from her audiences, but she never realized its origin as a hymn; by the time she was singing it in the 1960s she said it had "developed a life of its own".[68] It even made an appearance at the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969 during Arlo Guthrie's performance.[69]

Collins decided to record it in the late 1960s amid an atmosphere of counterculture introspection; she was part of an encounter group that ended a contentious meeting by singing "Amazing Grace" as it was the only song to which all the members knew the words. Her producer was present and suggested she include a version of it on her 1970 album Whales & Nightingales. Collins, who has a history of alcohol abuse, claimed that the song was able to "pull her through" to recovery.[3] It was recorded in St. Paul's, the chapel at Columbia University, chosen for the acoustics. She chose an a cappella arrangement that was close to Edwin Othello Excell's, accompanied by a chorus of amateur singers who were friends of hers. Collins connected it to the Vietnam War, to which she objected: "I didn't know what else to do about the war in Vietnam. I had marched, I had voted, I had gone to jail on political actions and worked for the candidates I believed in. The war was still raging. There was nothing left to do, I thought ... but sing 'Amazing Grace'."[70] Gradually and unexpectedly, the song began to be played on the radio, and then be requested. It rose to number 15 on the Billboard Hot 100, remaining on the charts for 15 weeks,[71] as if, she wrote, her fans had been "waiting to embrace it".[72] In the UK, it charted 8 times between 1970 and 1972, peaking at number 5 and spending a total of 75 weeks on popular music charts.[73]

For the three minutes that song is going on, everybody is free. It just frees the spirit and frees the person.

Although Collins used it as a catharsis for her opposition to the Vietnam War, two years after her rendition, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, senior Scottish regiment of the British Army, recorded an instrumental version featuring a bagpipe soloist accompanied by a pipe and drum band. The tempo of their arrangement was slowed to allow for the bagpipes, but it was based on Collins': it began with a bagpipe solo introduction similar to her lone voice, then accompanied by the band of bagpipes and horns, where in her version she is backed up by a chorus. It hit number 1 in the UK singles chart, spending 24 weeks total on the charts (the best-selling single in the UK in 1972[74]) and rose as high as number 11 in the U.S.[75][76] As of 2002, it was the best-selling instrumental record in British history, and a controversial one, as it combined pipes with a military band. The pipe president of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards was summoned to Edinburgh Castle and chastised for demeaning the bagpipes.[77]

Aretha Franklin and Rod Stewart also recorded "Amazing Grace" around the same time, and both of their renditions were popular.[note 9] All four versions were marketed to distinct types of audiences thereby assuring its place as a pop song.[78] Johnny Cash recorded it on his 1975 album Sings Precious Memories, dedicating it to his older brother Jack, who had been killed in a mill accident when they were boys in Dyess, Arkansas. Cash and his family sang it to themselves while they worked in the cotton fields following Jack's death. Cash often included the song when he toured prisons, saying "For the three minutes that song is going on, everybody is free. It just frees the spirit and frees the person."[3]

The U.S. Library of Congress has a collection of 3,000 versions of "Amazing Grace", some of which were first-time recordings by folklorists Alan and John Lomax, a father and son team who in 1932 traveled thousands of miles across the South to capture the different regional styles of the song. More contemporary versions include samples from such popular music groups as Sam Cooke and The Soul Stirrers (1963), The Byrds (1970), Elvis Presley (1971), Skeeter Davis (1972), Amazing Rhythm Aces (1975), Willie Nelson (1976), and The Lemonheads (1992).[62]

[edit] Popular use

Somehow, "Amazing Grace" [embraced] core American values without ever sounding triumphant or jingoistic. It was a song that could be sung by young and old, Republican and Democrat, Southern Baptist and Roman Catholic, African American and Native American, high-ranking military officer and anticapitalist campaigner.

Following the appropriation of the hymn in secular music, "Amazing Grace" became such an icon in American culture that it has been used for a variety of secular purposes and marketing campaigns, placing it in danger of becoming a cliché. It has been mass produced on souvenirs, lent its name to a Superman villain, appeared on The Simpsons to demonstrate the redemption of a murderous character named Sideshow Bob, incorporated into Hare Krishna chants and adapted for Wicca ceremonies.[80] The hymn has been employed in several films, including Alice's Restaurant, Coal Miner's Daughter, and Silkwood. It is referenced in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, which highlights Newton's influence on the leading British abolitionist William Wilberforce. The 1982 science fiction film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan used "Amazing Grace" amid a context of Christian symbolism, to memorialize the death of Mr. Spock[81] but more practically because the song has become "instantly recognizable to many in the audience as music that sounds appropriate for a funeral" according to a Star Trek scholar.[82] Since 1954 when an organ instrumental of "New Britain" became a bestseller, "Amazing Grace" has been associated with funerals and memorial services.[83] It has become a song that inspires hope in the wake of tragedy, becoming a sort of "spiritual national anthem" according to authors Mary Rourke and Emily Gwathmey.[84] It has been played following American national disasters such as the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, the Oklahoma City bombing, and the September 11 attacks.

[edit] Modern interpretations

In recent years, the words of the hymn have been changed in some religious publications to downplay a sense of imposed self-loathing by its singers. The second line, "That saved a wretch like me!" has been rewritten as "That saved and strengthened me", "save a soul like me", or "that saved and set me free".[85] Kathleen Norris in her book Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith characterizes this transformation of the original words as "wretched English" making the line that replaces the original "laughably bland".[86] Part of the reason for this change has been the altered interpretations of what wretchedness and grace means. Newton's Calvinistic view of redemption and divine grace formed his perspective that he considered himself a sinner so vile that he was unable to change his life or be redeemed without God's help. Yet his lyrical subtlety, in Steve Turner's opinion, leaves the hymn's meaning open to a variety of Christian and non-Christian interpretations.[87] "Wretch" also represents a period in Newton's life when he saw himself outcast and miserable, as he was when he was enslaved in Sierra Leone; his own arrogance was matched by how far he had fallen in his life.[88]

The communal understanding of redemption and human self-worth has changed since Newton's time. Since the 1970s, self-help books, psychology, and some modern expressions of Christianity have viewed this disparity in terms of grace being an innate quality within all people who must be inspired or strong enough to find it: something to achieve. In contrast to Newton's vision of wretchedness as his willful sin and distance from God, wretchedness has instead come to mean an obstacle of physical, social, or spiritual nature to overcome in order to achieve a state of grace, happiness, or contentment. Since its immense popularity and iconic nature, "grace" and the meaning behind the words of "Amazing Grace" have become as individual as the singer or listener.[89] Bruce Hindmarsh suggests that the secular popularity of "Amazing Grace" is due to the absence of any mention about God in the lyrics until the fourth verse (by Excell's version, the fourth verse begins "When we've been there ten thousand years"), and that the song represents the ability of humanity to transform itself instead of a transformation taking place at the hands of God. "Grace", however, to John Newton had a clearer meaning, as he used the word to represent God or the power of God.[90]

The transformative power of the song was investigated by journalist Bill Moyers in a documentary released in 1990. Moyers was inspired to focus on the song's power after watching a performance at Lincoln Center, where the audience consisted of Christians and non-Christians, and he noticed that it had an equal impact on everybody in attendance, unifying them.[22] James Basker also acknowledged this force when he explained why he chose "Amazing Grace" to represent a collection of anti-slavery poetry: "there is a transformative power that is applicable...: the transformation of sin and sorrow into grace, of suffering into beauty, of alienation into empathy and connection, of the unspeakable into imaginative literature."[91]

Moyers interviewed Collins, Cash, opera singer Jessye Norman, Appalachian folk musician Jean Ritchie and her family, white Sacred Harp singers in Georgia, black Sacred Harp singers in Alabama, and a prison choir at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. Collins, Cash, and Norman were unable to discern if the power of the song came from the music or the lyrics. Norman, who once notably sang it at the end of a large outdoor rock concert for Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday, stated, "I don't know whether it's the text—I don't know whether we're talking about the lyrics when we say that it touches so many people—or whether it's that tune that everybody knows." A prisoner interviewed by Moyers explained his literal interpretation of the second verse: "'Twas grace that taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved" by saying that the fear became immediately real to him when he realized he may never get his life in order, compounded by the loneliness and restriction in prison. Gospel singer Marion Williams summed up its effect: "That's a song that gets to everybody".[3]

The Dictionary of American Hymnology claims it is included in over a thousand published hymnals, but recommends its use for "occasions of worship when we need to confess with joy that we are saved by God's grace alone; as a hymn of response to forgiveness of sin or as an assurance of pardon; as a confession of faith or after the sermon."[4]

[edit] Notes

- ^ Stripped of his rank, whipped in public, and subjected to the abuses directed to prisoners and other press-ganged men in the Navy, he demonstrated insolence and rebellion during his service for the next few months, remarking that the only reason he did not murder the captain or commit suicide was because he did not want Polly to think badly of him. (Martin [1950], pp. 41–47.)

- ^ Newton kept a series of detailed journals as a slave trader; these are perhaps the first primary source of the Atlantic slave trade from the perspective of a merchant. (Moyers). Women, naked or nearly so, upon their arrival on ship were claimed by the sailors, and Newton alluded to sexual misbehavior in his writings that has since been interpreted by historians to mean that he, along with other sailors, took whomever he chose. (Martin [1950], pp. 82-85)(Aitken, p. 64.)

- ^ Newton's father was friends with Joseph Manesty, who intervened several times in Newton's life. Newton was supposed to go to Jamaica on Manesty's ship, but missed it while he was with the Catletts. When Newton's father got his son's letter detailing his conditions in Sierra Leone, he asked Manesty to find Newton. Manesty sent the Greyhound, which traveled along the African coast trading at various stops. An associate of Newton lit a fire signaling to ships he was interested in trading only 30 minutes before the Greyhound appeared. (Aitken, pp. 34–35, 64–65.)

- ^ Several retellings of Newton's life story claim that he was carrying slaves during the voyage in which he experienced his conversion, but the ship was carrying livestock, wood, and beeswax from the coast of Africa.

- ^ When Newton began his journal in 1750, not only was slave trading seen as a respectable profession by the majority of Britons, its necessity to the overall prosperity of the kingdom was communally understood and approved. Only Quakers, who were much in the minority and perceived as eccentric, had raised any protest about the practice. (Martin and Spurrell [1962], pp. xi–xii.)

- ^ Newton's biographers and Newton himself does not put a name to this episode other than a "fit" in which he became unresponsive, suffering dizziness and a headache. His doctor advised him not to go to sea again, and Newton complied. Jonathan Aitken called it a stroke or seizure, but it is unknown what caused it. (Martin [1950], pp. 140–141.)(Aitken, p. 125.)

- ^ Watts had previously written a hymn named "Alas! And Did My Saviour Bleed" that contained the lines "Amazing pity! Grace unknown!/ And love beyond degree!". Philip Doddridge, another well-known hymn writer wrote another in 1755 titled "The Humiliation and Exaltation of God's Israel" that began "Amazing grace of God on high!" and included other similar wording to Newton's verses. Newton biographer Jonathan Aitken states that Watts had inspired most of Newton's compositions. (Turner, pp. 82–83.)(Aitken, pp. 28–29.)

- ^ Only since the 1950s has it gained some popularity in the UK; not until 1964 was it published with the music most commonly associated with it. (Noll and Blumhofer, p. 8)

- ^ Franklin's version is a prime example of "long meter" rendition: she sings several notes representing a syllable and the vocals are more dramatic and lilting. Her version lasts over ten minutes in comparison to the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards' that lasts under three minutes. (Tallmadge)(Turner, pp. 150–151.)

[edit] Citations

- ^ Chase, p. 181.

- ^ a b Aitken, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e Moyers, Bill (director). Amazing Grace with Bill Moyers, Public Affairs Television, Inc. (1990).

- ^ a b c Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound, Dictionary of American Hymnology. Retrieved on October 31, 2009.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Newton (1824), p. 12.

- ^ Newton (1824), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Martin (1950), p. 23.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Martin (1950), p. 63.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Newton (1824), p. 41.

- ^ Martin (1950, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Martin (1950), p. 73.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 82–85.

- ^ Aitken, p. 125.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 166–188.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 198–200.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 208–217.

- ^ a b Pollock, John (2009). "Amazing Grace: The great Sea Change in the Life of John Newton", The Trinity Forum Reading, The Trinity Forum.

- ^ Turner, p. 76.

- ^ Aitken, p. 28.

- ^ a b Turner, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Benson, p. 339.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 6.

- ^ Benson, p. 338.

- ^ Aitken, p. 226.

- ^ Phipps, William (Summer 1990). " 'Amazing Grace' in the hymnwriter's life", Anglican Theological Review, 72 (3), pp. 306–313.

- ^ a b Basker, p. 281.

- ^ Aitken, p. 231.

- ^ a b Aitken, p. 227.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 8.

- ^ Turner, p. 81.

- ^ a b Watson, p. 215.

- ^ Aitken, p. 228.

- ^ Turner, p. 86.

- ^ Julian, p. 55.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 10.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Turner, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Turner, p. 117.

- ^ The Hymn Tune Index, Search="Hephzibah". University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana Library website. Retrieved on December 31, 2010.

- ^ Turner, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Turner, p. 123.

- ^ Bradley, p. 35.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 11.

- ^ Turner, p. 124.

- ^ a b Turner, p. 126.

- ^ Stowe, p. 417.

- ^ Aitken, p. 235.

- ^ Watson, p. 216.

- ^ Turner, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Patterson, p. 137.

- ^ Sutton, Brett (January 1982). "Shape-Note Tune Books and Primitive Hymns", Ethnomusicology, 26 (1), pp. 11–26.

- ^ Turner, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 13.

- ^ Turner, pp. 137–138, 140–145.

- ^ Allmusic search=Amazing Grace Song, Allmusic. Retrieved on January 5, 2011.

- ^ Turner, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Amazing Grace: Special Presentation: Amazing Grace Timeline United States Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia. Retrieved on November 1, 2008.

- ^ Tallmadge, William (May 1961). "Dr. Watts and Mahalia Jackson: The Development, Decline, and Survival of a Folk Style in America", Ethnomusicology, 5 (2), pp. 95–99.

- ^ Turner, p. 157.

- ^ "Mahalia Jackson." Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 9: 1971–1975. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1994.

- ^ Turner, p. 148.

- ^ Aitken, p. 236.

- ^ Turner, p. 162.

- ^ Turner, p. 175.

- ^ Collins, p. 165.

- ^ Whitburn, p. 144.

- ^ Collins, p. 166.

- ^ Brown, Kutner, and Warwick p. 179.

- ^ Scott, Robert (2002) 'ABBA: Thank You for the Music - The Stories Behind Every Song', Carlton Books Limited: Great Britain, p.24

- ^ Brown, Kutner, and Warwick p. 757.

- ^ Whitburn, p. 610.

- ^ Turner, p. 188.

- ^ Turner, p. 192.

- ^ Turner, p. 205.

- ^ Turner, pp. 195–205.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 15.

- ^ Porter and McLaren, p. 157.

- ^ Turner, p. 159.

- ^ Rourke and Gwathmey, p. 108.

- ^ Saunders, William (2003). Lenten Music Arlington Catholic Herald. Retrieved on February 7, 2010.

- ^ Norris, p. 66.

- ^ Turner, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Bruner and Ware, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Turner, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 16.

- ^ Basker, p. xxxiv.

[edit] Bibliography

- Aitken, Jonathan (2007). John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace, Crossway Books. ISBN 1581348484

- Basker, James (2002). Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems About Slavery, 1660–1810, Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09172-9

- Benson, Louis (1915). The English Hymn: Its Development and Use in Worship, The Presbyterian Board of Publication, Philadelphia.

- Bradley, Ian (ed.)(1989). The Book of Hymns, The Overlook Press. ISBN 0879543462

- Brown, Tony; Kutner, Jon; Warwick, Neil (2000). Complete Book of the British Charts: Singles & Albums, Omnibus. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8

- Bruner, Kurt; Ware, Jim (2007). Finding God in the Story of Amazing Grace, Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-4143-1181-8

- Chase, Gilbert (1987). America's Music, From the Pilgrims to the Present, McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-252-00454-X

- Collins, Judy (1998). Singing Lessons: A Memoir of Love, Loss, Hope, and Healing , Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-02745-X

- Julian, John (ed.)(1892). A Dictionary of Hymnology, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- Martin, Bernard (1950). John Newton: A Biography, William Heineman, Ltd., London.

- Martin, Bernard and Spurrell, Mark, (eds.)(1962). The Journal of a Slave Trader (John Newton), The Epworth Press, London.

- Newton, John (1811). Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, Samuel Whiting and Co., London.

- Newton, John (1824). The Works of the Rev. John Newton Late Rector of the United Parishes of St. Mary Woolnoth and St. Mary Woolchurch Haw, London: Volume 1, Nathan Whiting, London.

- Noll, Mark A.; Blumhofer, Edith L. (eds.) (2006). Sing Them Over Again to Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America, University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1505-5

- Norris, Kathleen (1999). Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith, Riverhead. ISBN 1-57322-078-7

- Patterson, Beverly Bush (1995). The Sound of the Dove: Singing in Appalachian Primitive Baptist Churches, University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02123-1

- Porter, Jennifer; McLaren, Darcee (eds.)(1999). Star Trek and Sacred Ground: Explorations of Star Trek, Religion, and American Culture, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-585-29190-X

- Rourke, Mary; Gwathmey, Emily (1996). Amazing Grace in America: Our Spiritual National Anthem, Angel City Press. ISBN 1-883318-30-0

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1899). Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life Among the Lowly, R. F. Fenno & Company, New York City.

- Turner, Steve (2002). Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-000219-0

- Watson, J. R. (ed.)(2002). An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-826973-0

- Whitburn, Joel (2003). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles, 1955–2002, Record Research, Inc. ISBN 0-89820-155-1

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Amazing Grace |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- U.S. Library of Congress Amazing Grace collection

- Cowper & Newton Museum in Olney, England

- Amazing Grace: Some Early Tunes Anthology of the American Hymn-Tune Repertory

| Preceded by "Without You" by Nilsson | UK number one single (Royal Scots Dragoon Guards version) 15 April 1972 for five weeks | Succeeded by "Metal Guru" by T. Rex |

Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" es un himno cristiano escrito por el clérigo y poeta inglés John Newton (1725-1807) y publicado en 1779. La composición, una de las canciones más conocidas en los países de habla inglesa, transmite el mensaje cristiano de que el perdón y la redención es posible a pesar de los pecados cometidos por el ser humano y de que el alma puede salvarse de la desesperación mediante la Gracia de Dios.

Newton escribió la letra a partir de su experiencia personal. Educado sin ninguna convicción religiosa, a lo largo de su juventud vivió varias coincidencias y giros inesperados, muchos de ellos provocados por su recalcitrante insubordinación. Fue forzado a unirse a la Royal Navy y, como marinero, participó en el mercado de esclavos. Durante una noche, una tormenta golpeó tan fuertemente su embarcación que, aterrorizado, imploró la ayuda de Dios, un momento que marca el comienzo de su conversión espiritual. Su carrera como tratante de esclavos duró algunos años más, hasta que abandonó la marina para estudiar teología.

Ordenado sacerdote de la Iglesia de Inglaterra en 1764, Newton fue nombrado párroco de Olney (Buckinghamshire), donde comenzó a componer himnos junto al poeta William Cowper. "Amazing Grace" fue escrito para ilustrar un sermón en el día de Año Nuevo de 1773. No se sabe si había música para acompañar los versos, puesto que pudo ser recitado por los feligreses sin melodía. Fue impreso por primera vez en 1779 dentro de la colección de Himnos de Olney de Newton y Cowper. A pesar de ser relativamente desconocido en Inglaterra, "Amazing Grace" fue usado extensamente durante el Segundo Gran Despertar en Estados Unidos a comienzos del siglo XIX. La letra ha sido adaptada a más de veinte melodías, si bien la más conocida y frecuente en la actualidad es la llamada "New Britain", que fue unida al poema en 1835.

El autor Gilbert Chase ha escrito que "Amazing Grace" es «sin lugar a dudas, el más famoso de todos los himnos populares», mientras que Jonathan Aitken, biógrafo de Newton, estima en su obra que el himno es representado cerca de diez millones de veces cada año. Ha tenido una particular influencia en la música folk y es un cántico emblemático de los espirituales americanos. "Amazing Grace" contempló un resurgir de su popularidad en los Estados Unidos durante la década de 1960 y desde entonces ha sido interpretado miles de veces, siendo un clásico de los cancioneros populares dentro de los países de habla anglosajona.

Contenido[ocultar] |

[editar] La conversión de John Newton

| «How industrious is Satan served. I was formerly one of his active undertemptors and had my influence been equal to my wishes I would have carried all the human race with me. A common drunkard or profligate is a petty sinner to what I was». «Qué industriosamente es servido Satán. Yo era entonces uno de sus activos tentadores y si mi influencia hubiera sido igual a mis deseos me habría llevado a toda la raza humana conmigo. Un borracho común o un despilfarrador es un débil pecador comparado con lo que yo era». |

| John Newton, 1778.[1] |

De acuerdo con el Dictionary of American Hymnology "Amazing Grace" es la autobiografía espiritual de John Newton en verso.[2] Newton nació en 1725 en Wapping, un distrito londinense cerca del Támesis. Su padre era un comerciante naval que había sido educado como católico pero mostraba simpatía por el pensamiento protestante, mientras que su madre era una devota cristiana independiente, no afiliada con la Iglesia anglicana. Desde el nacimiento de Newton su madre quiso que fuera clérigo, pero murió de tuberculosis cuando el niño tenía seis años.[3] Newton fue educado el resto de su infancia por una madrastra distante, mientras su padre estaba en el mar, y acudió a un internado, donde fue maltratado.[4] Con once años se unió a su padre en un barco como aprendiz, pero su incipiente carrera naval estaría marcada desde el comienzo por su testaruda desobediencia.

Según sus propias palabras, Newton escogió desde joven «un camino de muerte, alejado de Dios y lleno de malos hábitos».[5] Como marinero, renunció a su fe influenciado por un compañero con el que discutía acerca del libro Characteristicks, de Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3er conde de Shaftesbury. En una serie de cartas que escribió después, afirma:

| «Like an unwary sailor who quits his port just before a rising storm, I renounced the hopes and comforts of the gospel at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail me.» | «Como un marinero incauto que sale del puerto justo antes de una tormenta, renuncié a las esperanzas y consuelos del evangelio cuando todos los demás consuelos estaban a punto de abandonarme». |

Su padre le forzó a unirse a la Royal Navy por su continua desobediencia pero, tras abandonar su puesto en varias ocasiones, finalmente desertó para visitar a Mary «Polly» Catlett, una amiga de la familia de la que se había enamorado.[7] Tras la humillación pública que conllevó su deserción,[nota 1] consiguió ser transferido a un barco esclavista, donde comenzó su carrera como traficante de esclavos.[nota 2]

Newton se burlaba abierta y frecuentemente de la autoridad creando poemas obscenos y canciones sobre el capitán que se hicieron muy populares entre la tripulación.[8] Sus frecuentes conatos de rebelión le llevaron a ser castigado a la inanición hasta casi morir y a ser encarcelado en el mar y encadenado como los esclavos que transportaban, para finalmente ser obligado a trabajar en una plantación en Sierra Leona, cerca del río Sherbro.[9] Después de varios meses consideró la posibilidad de permanecer en Sierra Leona, pero su padre intervino tras recibir una carta de su hijo y fue rescatado casualmente por otro barco.[nota 3] Newton aceptó embarcarse de vuelta al Reino Unido, aunque declaró que su única razón era Polly.[10]

A bordo del Greyhound, Newton ganó notoriedad por ser el hombre más blasfemo de la tripulación. En un ambiente naval en el que los marineros usaban frecuentes juramentos, Newton fue castigado en muchas ocasiones no sólo por usar las peores palabras que había escuchado nunca el capitán, sino por crear neologismos que excedían su ya de por sí soez vocabulario.[11] En marzo de 1748, mientras el Greyhound estaba en el Atlántico Norte, una violenta tormenta azotó al barco provocando que un marinero, situado en un lugar donde justo antes había estado Newton, cayese por la borda.[nota 4] Tras horas de trabajo de achique de agua y creyendo que iban a volcar, Newton pidió desesperadamente al capitán que le dejase intentar algo, a lo que el oficial accedió. Según sus propias palabras, Newton afirmó: «Si esto no funciona, entonces ¡que el Señor tenga piedad de nosotros!».[12] [13] Volvió a la bomba y se ató, junto a otro marinero, a ella para impedir que fuese arrastrada por el agua. Tras una hora, volvió exhausto al puente de mando, donde reflexionó sobre lo ocurrido en las once horas siguientes.[14] Dos semanas después, el maltrecho barco y su hambrienta tripulación desembarcaron en Lough Swilly, Irlanda.

La tormenta y los hechos subsiguientes marcaron un antes y un después en la vida de Newton. Según sus propias palabras, desde semanas antes de la tormenta había estado leyendo The Christian's Pattern, un resumen de La imitación de Cristo, escrito por Tomás de Kempis en el siglo XV. El recuerdo de su frase durante la tormenta comenzó a obsesionarle y reflexionó profundamente acerca de si era merecedor de la Gracia de Dios o redimible después de no sólo abandonar la fe recibida, sino tras haberse opuesto directamente a ella, burlándose de otros creyentes, ridiculizando sus ritos y calificando a Dios como mito. Al cabo del tiempo llegó a convencerse de que Dios le había enviado un profundo mensaje y había comenzado a transformar su vida.[15]

La conversión de Newton, sin embargo, no fue inmediata. Anunció su intención de casarse con Polly, cuya familia, a pesar de que conocía su reputación, le permitió escribirle.[16] Volvió a alistarse en un barco esclavista de camino a África y allí siguió participando en las mismas actividades que antes, pero sin su habitual lenguaje. Su propósito de cambio personal se vio reforzado tras una grave enfermedad, pero su actitud ante la esclavitud seguía siendo la misma que la de sus contemporáneos[nota 5] y continuó comerciando con personas en varios viajes, algunos ríos arriba en África, «ahora como capitán», para vender los esclavos en los grandes puertos de América. Se casó con Polly en 1750 y participó en tres expediciones esclavistas más, pero abandonó la marina mercante con treinta años después de serle ofrecido el puesto de capitán en un barco no relacionado con el comercio de esclavos, al parecer tras sufrir una nueva crisis de salud.[17] [nota 6]

[editar] Sacerdote en Olney

A partir de 1756, mientras trabajaba como agente de aduanas en Liverpool, Newton empezó a aprender por su cuenta latín, griego y teología. Tanto él como Polly se vincularon con la comunidad eclesial de su parroquia, donde la pasión de Newton era tan impresionante que sus amigos le sugirieron que se preparase para el ministerio anglicano. Sin embargo, fue rechazado por el obispo de York en 1758, ostensiblemente por no tener un título universitario,[18] pero también por su cercanía al evangelismo y su tendencia a socializar con los metodistas.[19] Newton siguió con sus devociones y, después de ser animado por un amigo, escribió acerca de su experiencia en el comercio de esclavos y su conversión. George Legge, tercer conde de Dartmouth, impresionado por su historia, patrocinó la ordenación de Newton por el obispo de Lincoln y le ofreció la parroquia de Olney (Buckinghamshire) en 1764.[20]

[editar] Los Himnos de Olney

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound, |

| John Newton, Himnos de Olney, 1779 |

Olney era una barriada de cerca de 2.500 habitantes cuya principal industria era la fabricación artesanal de encaje. La mayor parte de la población era analfabeta y pobre.[21] La predicación de Newton fue desde el comienzo original, puesto que compartía desde el púlpito muchas de sus experiencias, mientras que lo habitual era que los clérigos hablasen desde la distancia, sin admitir ningún acercamiento al pecado o las tentaciones. Newton quiso vivir el día a día de sus parroquianos y era muy apreciado, a pesar de que sus escritos y expresión eran mejorables.[22] Era conocido por su devoción y dedicación; él mismo afirmaba que su misión era «romper los corazones duros y curar los rotos».[23] Trabó amistad con William Cowper, un escritor que había fracasado en su carrera como abogado y había sufrido brotes de locura, con varios intentos de suicidio. Vivió una experiencia de conversión similar a la de Newton y disfrutaba de su compañía. Juntos, el efecto sobre los feligreses fue impresionante: en 1768 comenzaron a celebrar una reunión de oración semanal para responder a un número cada vez mayor de parroquianos y escribieron lecciones para los niños del barrio.[24]

En parte por la influencia de Cowper y en parte por la costumbre de que los clérigos letrados escribieran versos, Newton comenzó a componer himnos utilizando el lenguaje popular de sus feligreses, lo que favoreció su distribución y comprensión. En la misma época florecieron otros prolíficos escritores de himnos religiosos, como Isaac Watts, cuyos himnos conocía Newton desde la infancia,[25] y Charles Wesley. El hermano de este último, John, que después sería el fundador del metodismo, había animado a Newton a entrar en el estado clerical. Watts, un pionero en la composición de himnos en lengua inglesa basados en los salmos bíblicos, había escrito previamente un himno titulado "Alas! And Did My Saviour Bleed" que contenía los versos "Amazing pity! Grace unknown!/ And love beyond degree!". Philip Doddridge, otro conocido autor de himnos escribió en 1755 otro himno titulado "The Humiliation and Exaltation of God's Israel" que comienza con los versos "Amazing grace of God on high!", además de otras similitudes con la obra de Newton. Los himnos más importantes de Watts estaban escritos según la medida común de 8.6.8.6, es decir, la primera línea es de ocho sílabas y la segunda es de seis.[26] Según el biógrafo Jonathan Aitken, Watts fue una gran influencia en muchas de las composiciones de Newton.[27] [28]

Newton y Cowper intentaron presentar un poema o un himno para cada encuentro semanal de oración. La letra de "Amazing Grace" fue escrita a finales de 1772 y probablemente utilizada para la oración el 1 de enero de 1773.[26] En 1779 se publicó anónimamente una colección de los poemas de ambos autores bajo el título de Himnos de Olney. Newton contribuyó con 280 de los 348 textos del libro. El poema que comienza con el verso «Amazing grace! How sweet the sound» está precedido del título «1 Chronicles 17:16-17, Faith's Review and Expectation».[2]

[editar] Análisis crítico

El impacto general de los Himnos de Olney fue inmediato y se convirtieron en una herramienta ampliamente utilizada por los predicadores evangélicos en Gran Bretaña durante muchos años. Los estudiosos apreciaban la poesía de Cowper más que el lenguaje sencillo de Newton, fruto de su fuerte personalidad. Los temas más comunes en los versos escritos por Newton en los himnos son la fe y la salvación, asombrándose de la Gracia divina y de su amor por Jesucristo, a través de exclamaciones de la alegría que sentía tras su conversión.[29] Como reflejo de la conexión de Newton con sus parroquianos, escribió muchos de sus versos en primera persona, reconociendo su propia experiencia de pecado. Bruce Hindmarsh, en su obra Sing Them Over Again To Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America considera "Amazing Grace" como un excelente ejemplo del estilo testimonial de Newton y del uso de su propia perspectiva.[30] En la época de publicación de los himnos, muchos fueron considerados grandes obras (no "Amazing Grace"), mientras que otros parecieron haber sido incluidos en la colección sólo para rellenar los huecos dejados por Cowper.[31] Jonathan Aitken considera a Newton, refiriéndose específicamente a "Amazing Grace", «un desvergonzado letrista de mediana cultura escribiendo para una congregación sin ninguna cultura», destacando que sólo 21 de las palabras utilizadas en las seis estrofas tienen más de una sílaba.[32]

William Phipps en el Anglican Theological Review y el autor James Basker han interpretado la primera afirmación de "Amazing Grace" como una prueba de que Newton consideraba su participación en el comercio de esclavos como su gran infamia, reflejando la opinión popular al respecto.[33] [34] De hecho, Newton unió fuerzas con un joven político idealista, William Wilberforce, miembro del Parlamento británico y principal impulsor de la campaña parlamentaria por la abolición de la esclavitud en el Imperio Británico, que culminó en la Slave Trade Act de 1807. Sin embargo, a pesar de que Newton se convirtió en un destacado abolicionista tras dejar Olney en la década de 1780, nunca conectó el himno que se convertiría en "Amazing Grace" con sus sentimientos contra la esclavitud.[35] Al mismo tiempo, completó su diario, actualmente perdido y que comenzó 17 años antes, dos después de abandonar el mar. La última entrada, de 1772, era un resumen de cuánto había cambiado hasta entonces.[36] Las letras de los Himnos de Olney fueron colocadas según su asociación con los versículos bíblicos que Newton y Cowper utilizaban en sus reuniones de oración y no tenían ningún objetivo político. Para Newton, el comienzo del año era una buena oportunidad para reflexionar sobre el propio progreso espiritual.

| «Entonces entró el rey David y estuvo delante de Jehová, y dijo: "Jehová Dios, ¿quién soy yo, y qué es mi casa, para que me hayas traído hasta este lugar? Y aun esto, Dios, te ha parecido poco, pues has hablado del porvenir de la casa de tu siervo, y me has mirado como a un hombre excelente, Jehová Dios"». |

| I Crónicas 17, 16-17. Traducción Reina-Valera. |

El título adscrito al himno, del Primer libro de las Crónicas, se refiere a la reacción del Rey David ante la profecía de Natán de que Dios mantendrá su heredad para siempre. La tradición teológica cristiana ha interpretado a menudo esta profecía como referida a Jesucristo, como descendiente de David, mesías prometido para la salvación de los pueblos.[37] El sermón de Newton el primer día de 1773 se centraba en la necesidad de expresar el propio agradecimiento a la guía de Dios, puesto que Dios está implicado en las vidas diarias de los creyentes aunque éstos no se den cuenta, de tal modo que la paciencia y la abnegación en las pruebas de cada día será recompensada en las prometidas glorias de la eternidad.[38] Newton se consideraba a sí mismo un pecador, como David, elegido sin merecerlo.[39] De acuerdo con el mismo Newton, los pecadores no arrepentidos estaban «cegados por el dios de este mundo» hasta que «la misericordia viene a nosotros no sólo sin merecerla o desearla (...) con nuestros corazones empeñados en callarla hasta que viene con el poder de su gracia».[36]

El Nuevo Testamento sirvió de base para la letra de "Amazing Grace". El primer verso, por ejemplo, está relacionado con la parábola del hijo pródigo, recogida en el evangelio de Lucas, donde el padre dice: «porque este hijo mío estaba muerto y vive de nuevo, estaba perdido y ha sido encontrado».[40] Por su parte, la historia del ciego curado por Jesús que dice a los fariseos que ahora puede ver procede del evangelio de Juan. Newton utiliza las palabras «Estaba ciego pero ahora veo» y declara «¡oh! qué gran deudor soy a la Gracia» en sus diarios y cartas desde 1752.[41] De acuerdo con Bruce Hindmarsh, el efecto de ambas estrofas en el himno permite un instante de liberación en la exclamación «¡Asombrosa Gracia!», que es inmediatamente seguida por la respuesta «qué dulce el sonido». En la obra An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, se califica a estas exclamaciones iniciales de «crudas pero efectivas» en una composición general que «sugiere una declaración de fe fuerte y simple».[39] La Gracia divina es invocada en tres ocasiones en los versos siguientes, culminando en la historia personal de Newton acerca de su conversión, en la línea indicada de testimonio personal.[30] La inestabilidad mental de Cowper volvió poco después de estrenarse el himno, por lo que Steve Turner, autor de Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, sugiere que Newton podía tener a su amigo en mente mientras componía la letra, al que dedicaría los temas de garantía de salvación por medio de la Gracia.[42]

[editar] Propagación

Aunque tiene sus raíces en Inglaterra, "Amazing Grace" se convirtió en una parte integral del tapiz cristiano en los Estados Unidos. Más de sesenta de los himnos de Newton y Cowper fueron reeditados en otras colecciones y revistas británicas, pero no así "Amazing Grace", que sólo apareció en una recopilación de 1780 patrocinada por Selina Hastings, Condesa de Huntingdon. El especialista John Julian recoge en su A Dictionary of Hymnology, publicado en 1892 que fuera de los Estados Unidos la canción era desconocida y que estaba «lejos de ser un buen ejemplo del mejor trabajo de Newton».[43] Entre 1789 y 1799 se publicaron cuatro variaciones del himno en los Estados Unidos en colecciones para congregaciones baptistas, congregacionalistas y reformadas holandesas.[37] Hacia 1830 los cancioneros presbiterianos y metodistas también incluyeron los versos de Newton.[44] [45] El himno, sin embargo, comenzó a ganar popularidad en el Reino Unido a partir de la década de 1950 y no fue hasta 1964 que se publicó con música.[46]

Las dos grandes influencias que ayudaron a la propagación de "Amazing Grace" en los Estados Unidos y lo convirtieron en un himno imprescindible en las celebraciones de muchas confesiones cristianas y regiones fueron el llamado Segundo Gran Despertar y el desarrollo de comunidades de canto de shape note. A comienzos del siglo XIX se vivió en Estados Unidos un gran movimiento religioso que hizo crecer las comunidades cristiana, comenzando en los estados de Kentucky y Tennessee. Multitudes sin precedentes se juntaban en celebraciones al aire libre, donde además de las habituales experiencias de salvación, las fogosas predicaciones se centraban en la salvación del pecador de la tentación y la reincidencia.[47] En muchas de las confesiones cristianas evangélicas las celebraciones se despojaron de ornamentos en beneficio de una mayor simplicidad, con cantos a menudo repetitivos, dirigidos a una población rural mayoritariamente pobre y analfabeta, a la que se quiso educar en la necesidad de apartarse del pecado. El testimonio personal se convirtió en un componente integral de estas reuniones, donde un miembro de la congregación o un extraño podía levantarse y contar su conversión desde una vida de pecado a otra de paz y piedad.[44] "Amazing Grace" era uno de los muchos himnos que se utilizaron para ilustrar estos sermones, frecuentemente acompañado de un estribillo simple y repetitivo, como el siguiente:

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind but now I see.

Shout, shout for glory,

Shout, shout aloud for glory;

Brother, sister, mourner,

All shout glory hallelujah.[47]

Simultáneamente, un movimiento independiente de canto comunal se estableció en los estados del sur y el oeste de Estados Unidos. En 1800 apareció un método de gran éxito para enseñar música a personas analfabetas, mediante el uso de cuatro sonidos para simbolizar la escala básica: fa-sol-la-fa-sol-la-mi-fa. Cada sonido está acompañado de una nota específica, por lo que fue conocido como música shape note. Las congregaciones se juntaban en grandes edificios durante días enteros de cantos, sentados en cuatro áreas diferentes rodeando un espacio abierto donde una persona dirigía al grupo como un todo. Mucha de la música adaptada a este método era religiosa, pero el propósito de estos cantos comunales no era primariamente espiritual. En muchos casos se rechazaba la música y se cantaba a capella, siguiendo el sentido de simplicidad propio del calvinismo de la época.[48]

[editar] La melodía "New Britain"